Peter Sloterdijk, the German philosopher and social critic, published an essay 25 years ago that became the subject of heated discussion in the learned salons. Reading it today, when it has just been published in a Danish translation, it is surprising that the compact, inaccessible text with its numerous references to Heidegger and Nietzsche as well as to the great thinkers of Antiquity could excite so many. Who cares about such things today?

In this way, Sloterdijk’s writing has proved prophetic. His 25-year-old assertion is that we no longer live under the taming and edifying influence of books, but have entered a completely new public sphere, to which new media do not provide the information that would at best enable the public to exercise judgment and make sensible collective decisions, but collectively tease us to death with an abundance of stimulants, entertainment and mass psychosis.

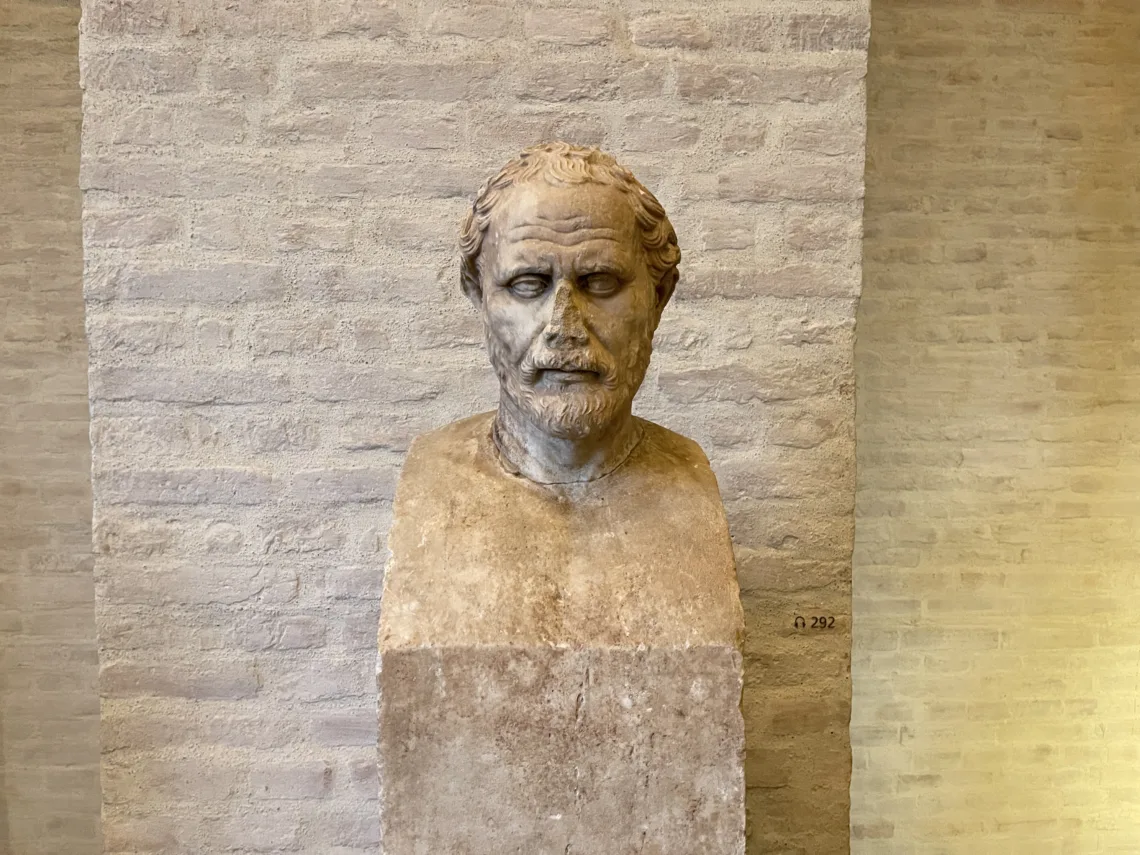

The ancient medium invented by the Greeks and Romans was the book. This humanistic genre not only strived for truth, but also wanted to influence and convince potential friends. According to Sloterdijk, the fact that literacy and the written text could remain relevant from its inception 2,500 years ago until recently is because the written word could be passed on as a “chain letter through generations”.

Knowing that humans are “animals under influence”, books were thick letters, sent to potential friends with what the senders perceived as the right kind of influence. The Romans – and later the Christians (whom Sloterdijk curiously does not mention at all) – participated in this battle for mankind and, with their developed transcription, were the mail carriers of Western civilization.

Civilization then rested on the recognition of two forces in the formation of man.

On the one hand, the inhibiting tendencies – and on the other hand, the liberating tendencies. Inhibiting sounds wrong today. But in European high culture, man was viewed differently: he was neither pure nor innocent, he was morally ambivalent. Inhibitions were also viewed more realistically: Man had to be tamed. Otherwise, nature or liberating influences would assert themselves and lead to decay and barbarism. The author writes: “The latent theme of humanism is thus to free man from his savagery, and its latent thesis is: proper reading makes tame.”

That was then. Now the notions are somewhat different.

In a historical light, the new media of our era come with the emergence of mass culture after World War I (radio), World War II (television) and most recently with the Internet and artificial intelligence. They are the amphitheatres and stadiums of our time with their suction of sensation and intoxication. Here, every day is a new day, a new face, a new scandal, invention or technology. The pace is fast and very little sticks. I think many will recognize this feeling of flicker, affectation and shamelessness from their own mobile phone that seems to have grown along with their hand.

We are fascinated by the new media monsoon, of course we are, just as ancient mobs loved parades, executions and races. We can’t help ourselves and have long since become addicted to the superficial news stream and the global attention race. Quite quickly, our world has become “post-literate” and “post-humanist”.

The age of the book is simply over; the same is true of both classical and national education, which enjoyed a short-lived renaissance with the 19th and 20th centuries with bourgeois nation-state colleges, secondary schools and the canon of reading books. We no longer recognize through writing and the classics of Western civilization, but through images, sound and pop music: “Our modern societies can still only marginally produce their political and cultural synthesis through literary, written, humanistic media.”

Of course, this marginalization does not mean that books are no longer published, but the norm-setting books of the past have been reduced to a subculture. They are no longer part of what Sloterdijk calls the synthesis of culture and politics:

“The fact that the norm-setting books of the past have more and more ceased to be letters to friends, and that they no longer lie on the desks and bedside tables of their readers, but have sunk into the timelessness of archives – this too has deprived the humanist movement of most of its former power (…) Everything indicates that archivists and activists have become the successors of humanists.”

Archivists and activists. Let me guess, the activists will win. Maybe even the ones Hans Rustad portrays in his latest piece on the conflict in Gaza and the pro-Palestinian youth in European capitals (11/6): Those who no longer value our lives. Those who stand up for the other, the oppressed, the noble savages, Hamas, Palestine, the blacks, the Global South.

Against such activists, humanists have neither words nor weapons.

Peter Sloterdijk: Rules for the Human Park – a response to Heidegger’s ‘Letter on Humanism’

Translated from German by Knud Michelsen

73 pages, 140 kr.

Multiverse